Spherical, which wraps a

flattened brain image

around a sphere.

Managing Data Using Higher Dimensions

|

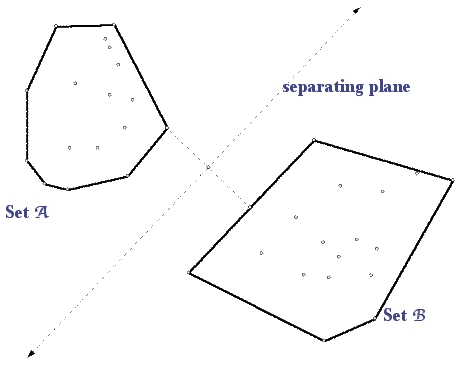

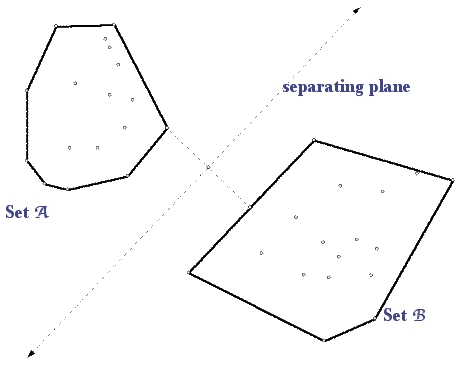

Data is collected for a large sample of individuals where

individuals have been assigned to one of two classes by experts.

Each individual corresponds to a point in an n-dimensional space

where n is the number of measurements recorded for each individual.

Mathematics is then used to

separate the classes via a plane, similar to the idea of linear

regression, but instead of finding a "best fit" line to all of the data,

we find the plane that best separates the data into classes.

|

|

New individuals are then classified and diagnosed

by a computer using

the separating plane.

Breast Cancer

When a tumor is found, it is important to

diagnose whether it is benign or cancerous.

In real-life,

9 attributes were

obtained via needle aspiration of a tumor such as clump thickness,

uniformity of cell size, and uniformity of cell shape.

The Wisconsin Breast Cancer Database used the data of

682 patients whose cancer status was known.

Since 9 attributes were measured, the data was contained in a

space that had 9 physical dimensions.

A separating plane was obtained.

There has been 100% correctness on computer diagnosis of 131 new

(initially unknown) cases, so this method has been very successful.

Heart Disease - Be sure that you have read the text above before

performing this activity.

View the

description of the data.

Scroll down to number 7. Use this to identify

exactly which attributes were used in the analysis

by looking at their abbreviations and then scrolling down to

identify the meaning via the complete attribute documentation descriptions.

Find a partner.

One of you should read this page as the other follows the directions.

View the

real-life numerical data that

was actually used in the heart disease analysis.

Using Select All and then Copy under Edit, copy the numerical

data from this link.

Open up Word and paste the data into Word.

Under Edit, Replace all of the instances of , with ^t .

Then under Edit, Select All and then Copy.

Open up Excel and paste the data into Excel.

It may take a while since there is a lot of data.

Each column is a different dimensions worth of data. How many dimensions

is this space? Each patient is a different row. How many patients were

studied?

This data was the real data that was used to find a separating plane

in this higher dimensional data space.

New patients have since been diagnosed using this plane.

I wanted you to

see how you can place

it into Excel and to have some experience the actual

data that was used. It is not often that one gets the chance to do this,

because people rarely make their data sets available to others.

You may now quit Excel without saving your file and

you should continue reading on the lab web page.

Gluing Spaces to Obtain Possible Shapes for our Universe

Euclidean Universes

Spherical Universes

Hyperbolic Universes

Real-Life Attempts to Discover the Shape of Space

and Whether the Universe is Spherical, Hyperbolic or Euclidean

As we see above, the shape of space is directly related to

whether the space is Euclidean, spherical or hyperbolic.

Mathematicians are working with astronomers and physicists

in order to try to solve this problem.

Greek mathematicians were able to determine that the earth was

round without every leaving it.

What is the Shape of Space?

We hope to answer this most basic

question about our universe in a similar manner.

According to relativity, space is a higher dimensional dynamic medium that can curve in one of three ways, depending on the distribution of matter and energy within it. Because we are embedded in space, we cannot see the flexure directly but rather perceive it as gravitational attraction and geometric distortion of images. To determine which of the three geometries our universe has, astronomers have been measuring the density of matter and energy in the cosmos.

Many cosmologists expect the universe to be finite,

curving back around on itself.

Mach inferred that the amount of inertia a body experiences is proportional to the total amount of matter in the universe. An infinite universe would cause infinite inertia. Nothing could ever move.

In addition to Mach's argument, there is preliminary work in quantum cosmology, which attempts to describe how the universe emerged spontaneously from the void. Some such theories predict that a low-volume universe is more probable than a high-volume one. An infinite universe would have zero probability of coming into existence [see "Quantum Cosmology and the Creation of the Universe," by Jonathan J. Halliwell; Scientific American, December 1991]. Loosely speaking, its energy would be infinite, and no quantum fluctuation could muster such a sum.

Historically, the idea of a finite universe ran into its own obstacle: the apparent need for an edge. Aristotle argued that the universe is finite on the grounds that a boundary was necessary to fix an absolute reference frame, which was important to his worldview. But his critics wondered what happened at the edge. Every edge has another side. So why not redefine the "universe" to include that other side? German mathematician Georg F. B. Riemann solved the riddle in the mid-19th century. As a model for the cosmos, he proposed the hypersphere--the three-dimensional surface of a four-dimensional ball, just as an ordinary sphere is the two-dimensional surface of a three-dimensional ball. It was the first example of a space that is finite yet has no problematic boundary.

One might still ask what is outside the universe. But this question supposes that the ultimate physical reality must be a Euclidean space of some dimension. That is, it presumes that if space is a hypersphere, then that hypersphere must sit in a four-dimensional Euclidean space, allowing us to view it from the outside. Nature, however, need not cling to this notion. It would be perfectly acceptable for the universe to be a hypersphere and not be embedded in any higher-dimensional space. Such an object may be difficult to visualize, because we are used to viewing shapes from the outside. But there need not be an "outside."

Experiments

All the ways discussed above have been tried by astronomers, but, up to now (1999), none of the observations have been accurate enough to make a definite determination. However,

the MAP satellite

(and another more accurate one scheduled for a launch in 2007)

are designed to make an accurate map of the microwave background radiation.

An analysis of this map may provide the clues we need to definitely

determine the global geometry of space.

What is the 4th Physical Dimension?

We have heard that physicists think that the universe has many

more physical dimensions than we directly experience.

We can try and understand the 4th physical dimension by thinking about

how a 2D Marge can understand the 3rd physical dimension.

For example, when Homer disappears behind the bookcase,

or when she sees shadows of a rotating cube, she experiences

behavior that does not seem to make sense to her.

In fact, since it is 3D behavior, it does not make sense in 2D.

But, it is in this

indirect way that 2D Marge can gain an appreciation for 3D.

Similarly, we can use indirect ways

of trying to gain an appreciation

for the counterintuitive behavior of 4D objects.

.

When you are finished watching the movie, scroll down and click on the

right triangle image at the bottom of the page in order to move

on to the next part of the talk.

The last page reads "Conclusion: Web Sites

"

Click on the Back key, hold down, and go back to the shape of the universe

lab to continue reading.

.

When you are finished watching the movie, scroll down and click on the

right triangle image at the bottom of the page in order to move

on to the next part of the talk.

The last page reads "Conclusion: Web Sites

"

Click on the Back key, hold down, and go back to the shape of the universe

lab to continue reading.